by f. Luis CASASUS, General Superior of the men’s branch of the Idente missionaries

New York/Paris, November 15, 2020. | XXXIII Sunday in Ordinary Time.

Book of Proverbs 31: 10-13.19-20.30-31; 1Thessalonians 5: 1-6; Saint Matthew 25: 14-30.

The original meaning of today’s Parable of Talents is a reference to the scribes and Pharisees, because they had kept the gift of God for themselves instead of sharing with the nations. They had excluded sinners and pagans from the kingdom. By multiplying the laws and applying a legalistic observance of them, they not only protected their religion from being contaminated by others but they also excluded them. They fundamentally misunderstood the nature of what they had been given.

The Parable of the Talents has, of course, many possible readings and interpretations, but its two moral and mystical consequences are clear: what happens if we do not use the talents received and how God responds if we truly use them.

The regrets are for someone to misuse or not to use his talent. When it is misused, harm is brought upon himself and others. When it is not use, even what he has will be lost. We can ask ourselves why precisely the one who received the least was clumsy and therefore severely punished. Of course, this is not an unfair discrimination by the Master, but a portrait of what sometimes happens to some of us: we believe that what we possess is not very valuable, or is insufficient, or is difficult to make it produce. In any case, the problem is that we keep it to ourselves. Somehow, we bury it.

When we act (or rather, stop acting) in this way, what is revealed is our deep selfishness. Indeed, the servant who received a talent said he knew his Master’s demanding way of behaving, but he still did not want to bother putting the money in the bank. This servant knew that his Master was able to bear fruit where no one expected it, but he still did not want to set out. The punishment for making the talents of the Lord unproductive is the exclusion from his joy, it is the fact of not belonging today to the kingdom of God. In reality, it is a punishment that we impose on ourselves, by acting against our nature, within which lies compassion as the seed of the authentic mercy of the Gospel.

This story, even if it is only an anecdote between two geniuses, shows us the power of talents in action:

Einstein was an inveterate concert-goer. He attended the famous debut of violinist Yehudi Menuhin with the Berlin Philharmonic, in which the 13-year-old Menuhin was soloist in a programme of the Bach, Beethoven and Brahms concertos that would be nowadays inconceivable. Einstein was so moved by Menuhin’s playing that he rushed into the boy’s room after the performance and took him in his arms, exclaiming “Now I know that there is a God in heaven!”

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC) already intuited that happiness is, “not a habit or a trained faculty, but it is some exercise of a faculty”.

There are many obstacles for our talents to be put to use, so that they do bear fruit. Surely, the first difficulty is that we are not fully aware that we possess them. For that we have to understand that it is a talent. In our spiritual life, a talent is anything that can be put to the service of others, to bring them closer to God. Certainly, this includes the skills, the knowledge, the graces received, the strengths of each one… everything that of innate or acquired origin can be projected to others and can give them light and strength to come closer to God and to their neighbor.

In this, the devil’s subtle and destructive role is devastating, because he uses many mechanisms of our ego to make us indifferent, insensitive, and blind to the link between the needs of others and our talents.

Some of the sources of resistance to get started that are most likely to occur are:

* Fear of losing control, in the face of the uncertainty of what is new. That is why many of us limit ourselves to repeating what others have said or to carrying out the activities without changing anything “because it was always done that way”.

* Surprise. We are not prepared for change and, instead of preparing for the new situation, we entrench ourselves without considering the consequences. Situations catch us off guard. We lack courage in taking risks in the proclamation of the gospel. We are afraid, like the servant, of venturing to unknown territories.

* Doubts about ourselves, about our capacity and competence. Without realizing that we are not the center of the universe, nor do we have any idea of the graces we will receive.

In the book The Screwtape Letters, by C. S. Lewis, a devil briefs his demon nephew, Wormwood, in a series of letters, on the subtleties and techniques of tempting people. In his writings, the devil says that the objective is not to make people wicked but to make them indifferent. This higher devil cautions Wormwood that he must keep the patient comfortable at all costs. If he should start thinking about anything of importance, encourage him to think about his luncheon plans and not to worry so much because it could cause indigestion. And then the devil gives this instruction to his nephew: “I, the devil, will always see to it that there are bad people. Your job, my dear Wormwood, is to provide me with people who do not care.”

On the contrary, the First Reading is a song to a woman who certainly puts her talents to work, always at the service of other people and, in this case, with deep and feminine sensitivity to the effects of her actions on the others. It is the opposite of indifference: She reaches out her hands to the poor, and extends her arms to the needy.

Even more, a talent in ancient times was a measure of something particularly weighty, usually silver or gold. A single talent might represent as much as 50 pounds of gold or silver. A talent was a sum corresponding to the salary… of about twenty years of work by a worker.

The ancient Jewish reader would have caught immediately the connection to heaviness: a talent was weighty. Heaviness would have brought to mind the heaviest weight of all, which was rendered in Latin as the glory (gloria, in Latin) of God. In ancient culture, the image was clear: it is about what is consistent and solid as opposed to what is fleeting, light, what goes with the wind. One cannot look for security and peace in other things. That is why St. Paul says in the Second Reading: When people are saying, “Peace and security,” then sudden disaster comes upon them. And what was heaviest (most glorious) of all was the mercy of God.

The talents given to the three servants represent not so much personal capacities or skills; they are a share in the mercy of God, in the weightiness, the robustness of the divine love. Since mercy is always directed to the other, these “talents” are designed to be shared. In reality, they will increase precisely in the measure that they are given away. This explains why Christ in the Sermon on the Mount says that the merciful are blessed because they will receive mercy. That is the answer of the Holy Spirit: To everyone who has, more will be given and he will grow rich. Let us note that the talents are distributed “to each according to his ability” and therefore the fruit produced with the effort and mercy of each one is NOT expected to be the same.

Certainly, God has been merciful to us by giving us the means to practice and develop mercy. That includes good contacts, teachers, friends, counsellors, periods of good health, different forms of creativity and intelligence…and faith. The wisdom of this world and daily experience show us that different skills, like our muscles, deteriorate if we do not use them. On the contrary, their growth and development requires practice.

Novelist and Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) was once besieged by college students for a lecture on the art of writing. The students explained that they had a deep desire to be writers. Lewis began his lecture with: “How many of you earnestly yearn to be writers?” All hands went up. “Then,” said Lewis, “there is no point in lecturing to you. My advice to you is to go home and write, write, write!” Will we be able to apply the lesson to the grace of being merciful, which in always different ways we have all received?

This parable also teaches us, in all clarity, that it is God who has the initiative, who approaches us by putting in our hearts (also in the intelligence, in the body and in the soul) the talents that we need to participate in the kingdom of heaven from now on. One of the clearest and most visible proofs of his response to the one who uses his talents for the good of his neighbor is Beatitude. It means a state of peace that we recognize as indestructible. That is why in the OT and NT we find descriptions like the following:

Blessed is the man whose strength is in You, whose heart is set on pilgrimage (Psalm 84:5).

The Lord is a refuge for the oppressed, a stronghold in times of trouble (Psalm 9:9).

Give all your worries to him, because he cares for you (1 Peter 5:7).

Do not grieve, for the joy of the Lord is your strength (Nehemiah 8:10).

This form of peace does not mean being apart from the pain and difficulties of the world, but the certainty that no one can destroy it. At the same time, it is characterized because it is transmitted to others, as poetically expressed in the First Reading. A third characteristic of that Beatitude is that it redeems us from seeking peace and tranquility in the things of the world, as St. Paul says in the Second Reading.

How can we then use the talents? Surely, by being as cunning as snakes. There are people to whom this animal is repulsive, but for some reason Christ uses it as a model (Mt 10:16) for our behavior. Said in modern terms, but also in zoological terms: once the prey is located, it does not hesitate to throw itself at it. This is the unitive faculty in action, the center of our ascetic effort. Snakes are not only quick and cunning to hide, but also to move into action. The focus of the parable is not the profit made, but rather the attitude involved.

One of the main messages of the parable is in the master’s rebuke of the slothful servant: the only unacceptable attitude is the disengagement; it is the fear of risk. He is condemned because he let himself be blocked by fear. Most of our miseries come from negligence and irresponsibility. This was why the last servant was punished severely.

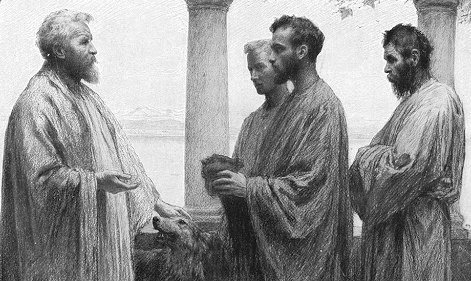

Image: Eugène Burnand |The Talents

!["El mundo puede cambiar desde el corazón"

(Papa Francisco, Encíclica Dilexit Nos)

"El Corazón de Cristo es éxtasis, es salida, es donación, es encuentro. En él nos volvemos capaces de relacionarnos de un modo sano y feliz, y de construir en este mundo el Reino de amor y de justicia. Nuestro corazón unido al de Cristo es capaz de este milagro social.

Tomar en serio el corazón tiene consecuencias sociales. Como enseña el Concilio Vaticano II, «tenemos todos que cambiar nuestros corazones, con los ojos puestos en el orbe entero y en aquellos trabajos que todos juntos podemos llevar a cabo para que nuestra generación mejore». Porque «los desequilibrios que fatigan al mundo moderno están conectados con ese otro desequilibrio fundamental que hunde sus raíces en el corazón humano». [21] Ante los dramas del mundo, el Concilio invita a volver al corazón, explicando que el ser humano «por su interioridad es, en efecto, superior al universo entero; a esta profunda interioridad retorna cuando entra dentro de su corazón, donde Dios le aguarda, escrutador de los corazones (cf. 1 S 16,7; Jr 17,10), y donde él personalmente, bajo la mirada de Dios, decide su propio destino».

Esto no significa confiar excesivamente en nosotros mismos. Tengamos cuidado: advirtamos que nuestro corazón no es autosuficiente; es frágil y está herido. Tiene una dignidad ontológica, pero al mismo tiempo debe buscar una vida más digna. Dice también el Concilio Vaticano II que «el fermento evangélico ha despertado y despierta en el corazón del hombre esta irrefrenable exigencia de la dignidad», aunque para vivir conforme a esa dignidad no nos basta conocer el Evangelio ni cumplir mecánicamente lo que nos manda. Necesitamos el auxilio del amor divino. Acudamos al Corazón de Cristo, ese centro de su ser, que es un horno ardiente de amor divino y humano y es la mayor plenitud que puede alcanzar lo humano. Allí, en ese Corazón es donde nos reconocemos finalmente a nosotros mismos y aprendemos a amar."](https://www.idente.org/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)